Systems Thinking in Research: Considering Interrelationships in Research Through Rich Pictures

Bob Williams, Joan O’Donnell

The third of a series of blogs on using systems thinking in doctoral research that were originally published on the ALL Institute Blog, Maynooth University based on training provided to ADVANCE CRT PhD students..

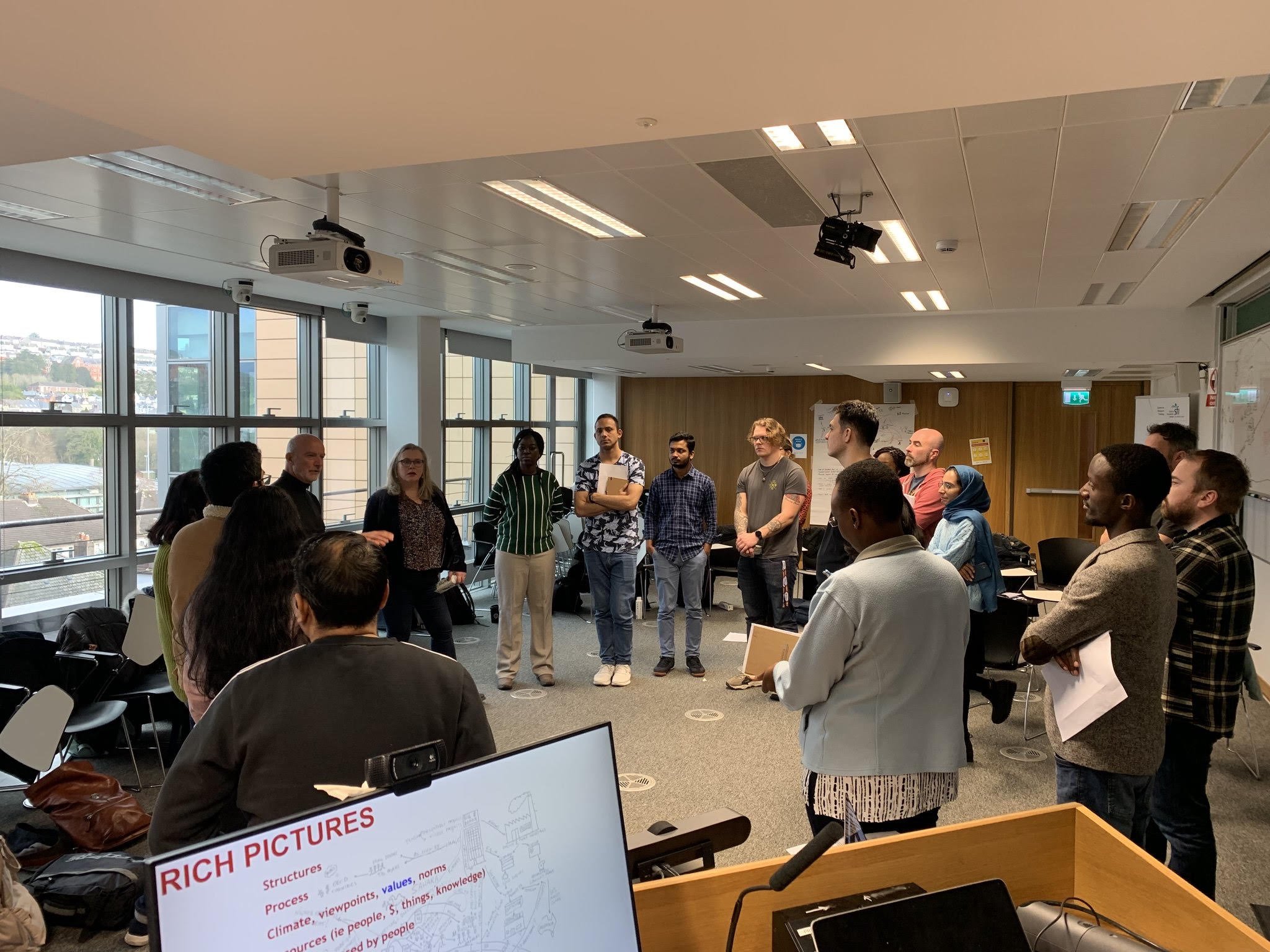

Bob and Joan with 1st year ADVANCE CRT Student Induction, Cork, Ireland January 2023

Let’s start with a true story. It follows on from our last blog about focus and scope. But it highlights our tendency to start with focusing in on the subject of our research — with boundary setting — rather than considering the wider scope, especially when faced with ‘a problem’ that we hope our research will address. Stating that something is a ‘problem’ is a form of boundary setting, as we will see.

Some years ago, Russ Ackoff, a leading systems thinker, was approached by a major machine tool manufacturer experiencing considerable fluctuations in demand for its products. This created problems of low morale, poor productivity and bad industrial relations. Russ was called in to sort out this issue which was framed by the company as a ‘production smoothing’ problem. The organisation’s senior management asked Russ to work out how it could smooth out its production so that it can avoid negotiating layoffs and then running around trying to recruit people some months later. After a considerable amount of investigation, Russ told them that they would never find a solution if they continued to see (i.e., frame or bound) the problem in terms of production smoothing.

However, he said, there may be a solution if the company framed the problem as a demand smoothing problem. To smooth demand, you needed to find a product that was counter-cyclical to the demand for the company’s existing product line. After much research, the company found that, not only was the demand for road-building equipment counter-cyclical to that for machine tools, it also required much of the same technology, labour skill-set, marketing and distribution as for manufacturing machine tools. The company accepted Russ’ recommendation and started manufacturing road-building equipment. This stabilised production and labour; it also considerably increased the company’s profit margins. Indeed, these days the company is better known for its road-building equipment than its other products.

How many times have you rushed, like managers at that company, into identifying ‘a problem’? Why not stand back, a bit like Russ suggested, and consider whether that really is the right way of responding to the situation that, for you, is problematic. Notice the difference in language. In systems language, a problematic situation is a situation that concerns or interests you for some reason. But that situation may contain many different ‘problems’; your initial choice of ‘the problem’ (a boundary choice) may not be the most appropriate focus for addressing the situation that concerns you.

So, what does systems thinking have to do with this issue?

Recall the diagram below from our previous blog:

Distinguishing between focus and scope in research

Even in a PhD you often start with focus on, for example, the key topic of your PhD project. But that already contains a series of boundary choices that provide the ‘lens’ through which you understand and subsequently explore the scope of your PhD. That company’s focus on ‘production’ led them to see and explore the scope of the issue only in ‘production’ terms. And that would prove to be unhelpful. It was only when it changed its focus to ‘demand’ could it then view the scope of the situation in ways that would lead to a solution. But it didn’t just pick the new focus at random. The new focus emerged by stepping back from the original focus and exploring a broader scope, inter-relationships and perspectives, that ultimately allowed Caterpillar to identify and narrow down on a more useful focus. Having done this, they were then able to cycle again around inter-relationships and perspectives to arrive at a particular solution, and in doing so they worked out what was feasible and desirable to do, to systemically address the problematic situation.

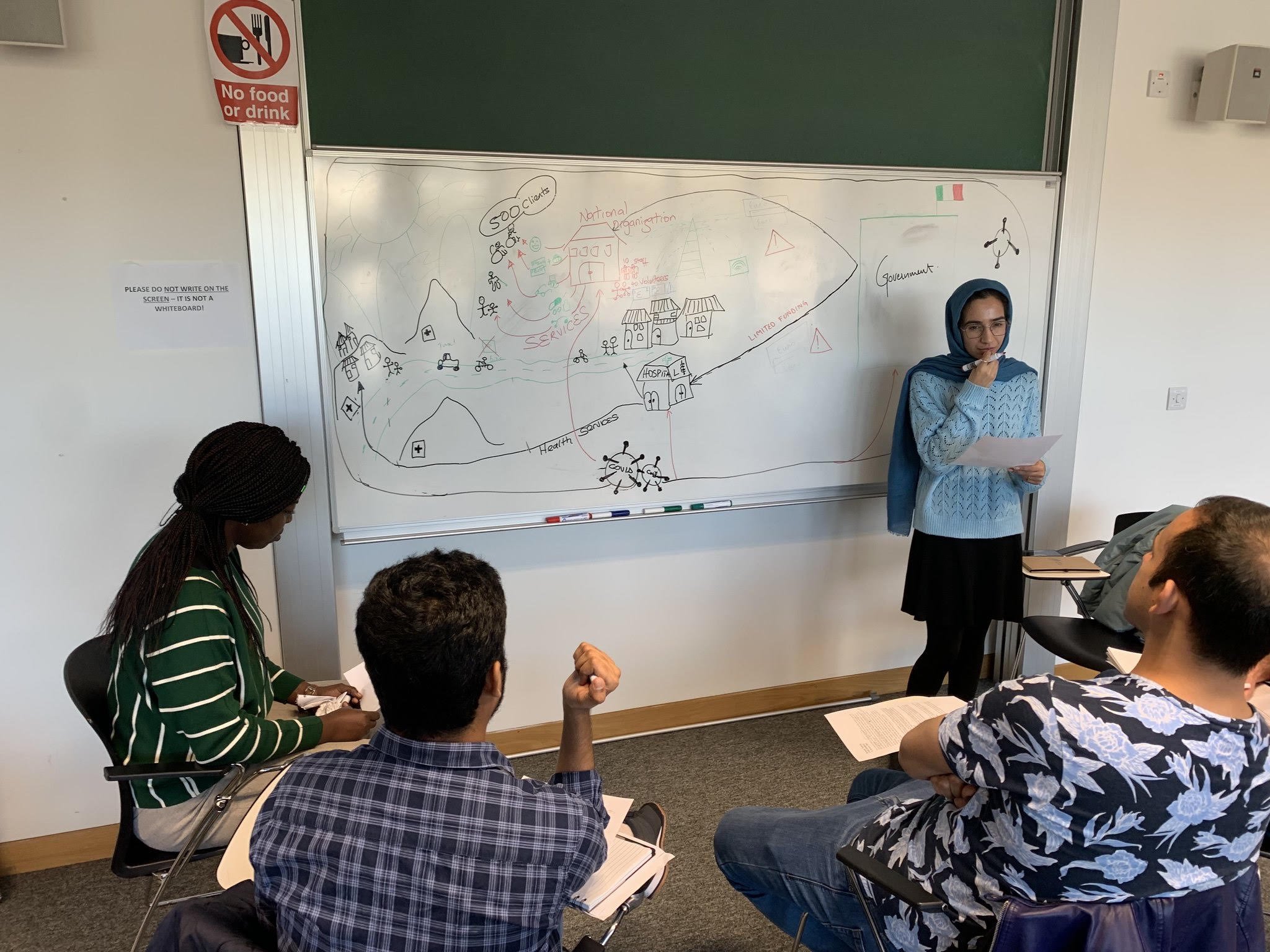

PhD Students from ADVANCE CRT Student Induction, Cork January 2023

So where do you start when exploring the scope for your research? Do you start at inter-relationships or do you start at perspectives? Do you start with ‘reality’ or people’s perceptions of ‘reality’? You will notice on the triangle diagram that the arrows go both ways, so, as long as you understand that the two are linked then it really doesn’t matter which you start with.

In this blog series, we will start with understanding inter-relationships and then move to engaging with the multiple perspectives that people have of reality.

So, what are the kinds of questions that a systemic inquiry into your research situation pose? Here are some examples:

What purposes does your research situation appear to be fulfilling?

Whose or what needs are and are not being addressed from your research?

How do the current and past actions address these needs (if at all)?

Which parts of your research situation have too many things to cope with compared with their ability to respond? How does that affect one’s ability to address the needs and achieve the benefits and purposes?

How does the information necessary to fulfil those needs flow around your research situation?

In what ways are the rules (what must be done), roles (who does what) and tools (things you use to do it – including language) operating within your research situation influencing the ability to fulfil those needs?

How do the tasks you have to do, the way your work is coordinated with others’ tasks, the overall management of your PhD, its responsiveness to things relevant things outside your PhD, work together?

What kind of puzzles and contradictions are there within your research? What are the consequences for whom?

How significant is the difference between what you feel you ought to do and what you are able to do? How can you manage that?

That’s a lot of complicated questions and there are many ways in which the systems field explores them. Diagrams are frequently used to do this. There are, of course, many kinds of diagrams. One that is especially good at exploring a complex situation is Rich Picturing.

Rich Pictures

Rich Pictures are part of a systems methodology called Soft Systems Methodology. A Rich Picture intends to visually represent as many of the following aspects of the situation of interest as possible:

What purposes does your research situation appear to be fulfilling?

Whose or what needs are and are not being addressed from your research?

How do the current and past actions address these needs (if at all)?

Which parts of your research situation have too many things to cope with compared with their ability to respond? How does that affect one’s ability to address the needs and achieve the benefits and purposes?

How does the information necessary to fulfil those needs flow around your research situation?

In what ways are the rules (what must be done), roles (who does what) and tools (things you use to do it — including language) operating within your research situation influencing the ability to fulfil those needs?

How do the tasks you have to do, the way your work is coordinated with others’ tasks, the overall management of your PhD, its responsiveness to things relevant things outside your PhD, work together?

What kind of puzzles and contradictions are there within your research? What are the consequences for whom?

How significant is the difference between what you feel you ought to do and what you are able to do? How can you manage that?

That’s a lot of complicated questions and there are many ways in which the systems field explores them. Diagrams are frequently used to do this. There are, of course, many kinds of diagrams. One that is especially good at exploring a complex situation is Rich Picturing.

Rich Pictures are part of a systems methodology called Soft Systems Methodology. A Rich Picture intends to visually represent as many of the following aspects of the situation of interest as possible:

The structure of the situation;

The processes between elements of that structure;

Important aspects of the situation that affect how the stakeholders, stakes, structures and processes interact;

The nature of the interrelationships (e.g., strong, weak, fast, slow, conflicted, collaborative, direct, indirect);

Purposes, aspirations, and goals;

Motivations;

Values and norms;

Environmental aspects, e.g., a climate of opinion;

Issues, conflicts, and agreements;

Resources (e.g., people, money, tools, skills);

Importantly, they need to illustrate things you don’t know or puzzle you. After all, why would you be doing research if you already knew the problem and solution.

Here is an example of a Rich Picture. It illustrates a problematic situation around rice production in Mali.

Rich Picture of a problematic situation related to rice production in the Sahel region of Mali (Bob Williams)

You will see that it is a mixture of pictures and text. This is deliberate. Sometimes, a picture tells a 1000 words – it is a shorthand that makes it possible for you to explore the entire scope of your work at a single glance.

Rich Pictures are often drawn before you know clearly which parts of a situation you should be focusing on. It is that ‘standing back’ phase, which helped Russ Ackoff change the framing of ‘the problem”. Therefore, when drawing a Rich Picture, free your mind as much as possible from any preconceived ideas you may have about the situation. People drawing Rich Pictures for the first time often try to place too much order too quickly into a situation. The drawing reflects any chaotic mess of thoughts and perceptions that pours down your arm from your brain, out of the pen in your hand and onto whatever surface you are using to draw the Rich Pictures. They can get very messy indeed, but often the messiest pictures are the richest and most meaningful.

Whatever it looks like, it is very important that the Rich Picture conveys all the important elements of a situation (see the above list) without overly imposing your own understandings and prejudices. In Rich Picturing, you are drawing the unstructured messiness of the problem that will allow you to think systemically about that situation.

Thus, Rich Pictures are a means for moving from a state of messy confusion, where all you know is that you’re dealing with a problematic situation, to a state where you’ve identified one or more potential foci that you want to address. But, before you finalise that, you need to explore the matter of how different people will interpret your Rich Picture and consider what that implies for your research focus. One approach is to bring other people into the Rich Picturing process to provide their own knowledge and perspective. This can be either your supervisor or other stakeholders directly involved in, or affected by, the situation. And that brings us to consider the value of exploring multiple perspectives that will ultimately help you decide your research focus.

This article was first published by the ALL Institute and has emanated from research supported in part by a Grant from Science Foundation Ireland under Grant number 18/CRT/6222. The opinions, findings and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Science Foundation Ireland.

For further information, you can contact Bob: bob@bobwilliams.co.nz or Joan: joan@systemsbeing.com.